What is Phytic Acid

Phytic acid is known as a food inhibitor. It binds micronutrients and prevents them from being bioavailable. (Gupta, Gangoliya, & Singh, 2015) This happens because we, humans, lack the enzyme phytase in our digestive tract. Soaking these foods high in phytic acid can help reduce the phytic acid content in foods to improve the nutritional value and decrease the digestive stress. Reducing phytic acid allows us to break down the food better and absorb more nutrition, thus increasing the bioavailability. The three most common methods to reduce phytic acid are: fermentation, soaking, and sprouting (germination). Soaking is the fastest and easiest way to increase bioavailability and energy from food. It is also the first step of sprouting which I will save for another post.

Why Would You Soak Grains, Nuts, Seeds, or Legumes?

Have you ever noticed digestive issues, bloating, or adverse reactions after eating nuts, seeds, or legumes? If so, do not be alarmed. It is actually very common. These raw foods have high amounts of phytic acid. Phytic acid is the storage form of phosphorus. It is only found in plant-based foods. Nuts, seeds, grains, beans, and legumes have larger amounts of phytic acid than other plant-based foods. Phytic acid binds to zinc, magnesium, calcium, and other minerals in these foods within the digestive tract if they are not soaked. (Pitchfork, 2002) The binding of these minerals to phytic acid can/will cause gastrointestinal irritability. When it binds with minerals in the digestive tract it is called a phytate. When phytates are present they can impair the absorption.

Now, a lot of people’s guts may not experience any issues. If someone has a healthy and balanced gut flora they will probably better handle increases of phytic acid from time to time. People who consume a largely plant-based diet may be at risk for mineral depletion if their gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) is constantly under absorbing nutrients needed. It is possible to be malnourished while still consuming the proper macro and micronutrients. Is there a way to inhibit or lessen phytic acid? You betcha! There are three common ways to decrease phytic acid and phytates: soaking, sprouting (germination), and fermentation.

Soaking

When foods high in phytic acid are soaked in salt water and then dehydrated it neutralizes the phytates. It germinates dormant energy, releases nutrients, and increases digestibility (Pitchfork, 2002) Technically speaking, it is undergoing dephosphorylation. Yes, it really is that simple. For example cashews are a softer nut and only require +/- six hours of soaking. A more dense nut, like an almond, would require 8-10+/- hours. Investing in a dehydrator is a must! I use this dehydrator for a multitude of things and it has never failed me. It has a classic on/off switch, so you can run it as long as you wish. You can also adjust the temperature anywhere from 95 F to 165 F. After soaking nuts, seeds, and legumes you will want to dehydrate them for at least 12 hours. I would recommend starting your dehydrator at 150 F for a few hours and make certain the nuts are actually drying out. If they are, you can turn the heat down for the remainder of the time. If you don’t have a dehydrator you may be able to use your oven at its lowest setting, 150-200F.

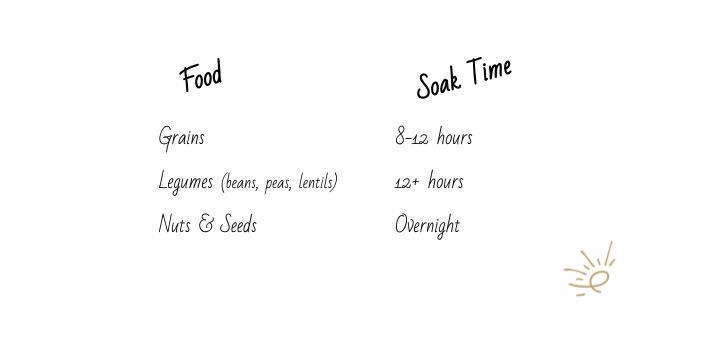

You can find specific soak times for each grain, legume, nut, and seed but the general rule of thumb I’ve experienced is below. Use common sense, the more dense or hard a nut, seed, grain, etc. is the longer it needs to soak. Another example: quinoa is a softer grain and can get by with being soaked for only two to four hours. Soaking even for a few hours is better than nothing at all. The longer the soak time the more dephosphorylation occurs = more bioavailable nutrients. Soaking nuts prior to making different nut milks is very popular! Check out Enlighten Life’s recipe for Vanilla Cashew Milk.

References

Gupta, R. K., Gangoliya, S. S., & Singh, N. K. (2015, February). Reduction of phytic acid and enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients in food grains. Retrieved December 09, 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25694676

Lopez, H. W., Leenhardt, F., Coudray, C. and Remesy, C. (2002), Minerals and phytic acid interactions: is it a real problem for human nutrition?. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 37: 727–739. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2621.2002.00618.x

Pitchford, P. (2002). Healing with whole foods: Asian traditions and modern nutrition (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Schlemmer, U., Frolich, W., Prieto, R. M., & Grases, F. (2009, September). Phytate in foods and significance for humans: Food sources, intake, processing, bioavailability, protective role and analysis. Retrieved November 01, 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19774556

Singh, R. P., & Agarwal, R. (2005, July/August). Prostate cancer and inositol hexaphosphate: Efficacy and mechanisms. Retrieved November 01, 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16080543

Urbano, G., Lopez-Jurado, M., Aranda, P., Vidal-Valverde, C., Tenorio, E., & Porres, J. (2000, September). The role of phytic acid in legumes: Antinutrient or beneficial function? Retrieved November 01, 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11198165

Vucenik, I., & Shamsuddin, A. M. (2006). Protection against cancer by dietary IP6 and inositol. Retrieved November 01, 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17044765

Comments (1)

[…] Phytic Acid […]

Comments are closed.